We are a medical relief and advocacy organization dedicated to providing health care to victims of armed violence and extreme poverty.

For the past twenty-five years we have achieved our mission by:

Developing sustainable medical and mental health programs in war zones and underserved communities world-wide driven by skilled volunteers and trained local health professionals.

Promoting women’s rights through women’s health programs that prevent disease and promote a healthy life-style.

Building alliances with social service partners to rehabilitate torture and trauma victims seeking asylum in the United States.

Bearing witness to human rights violations and advocating for social justice and access to medical care for victims of armed conflicts, political oppression, and state-sponsored torture.

Medicine for Peace (MFP) is a non-profit, tax-exempt (501 c 3), medical relief and humanitarian organization founded in 1991. The establishment of MFP was a direct response to the health crisis of Iraqi children following the Gulf War. Following the war in Iraq, MFP performed child nutrition assessments, established clinics, delivered drugs to hospitals in need, and brought children to the United States for life-saving surgery. We were expelled from Iraq in 1994 for reporting human rights abuses, but returned in 2004 to perform a damage assessment study of the largest public hospitals in Baghdad.

From 1995 to 2000, MFP developed and maintained a school-based mental health program for Bosnian Muslim children who were victims of the ethnic cleansing of the city of Kozarac. MFP physicians presented their findings concerning traumatized children to the first conference attended by both Muslims and Serbs after the Bosnian War. The celebrated Sarajevo newspaper, Oslobodjenje, praised the MFP program in an article entitled “Life Returns to Kozarac” describing it as model of cooperation between Bosnian women and American relief workers.

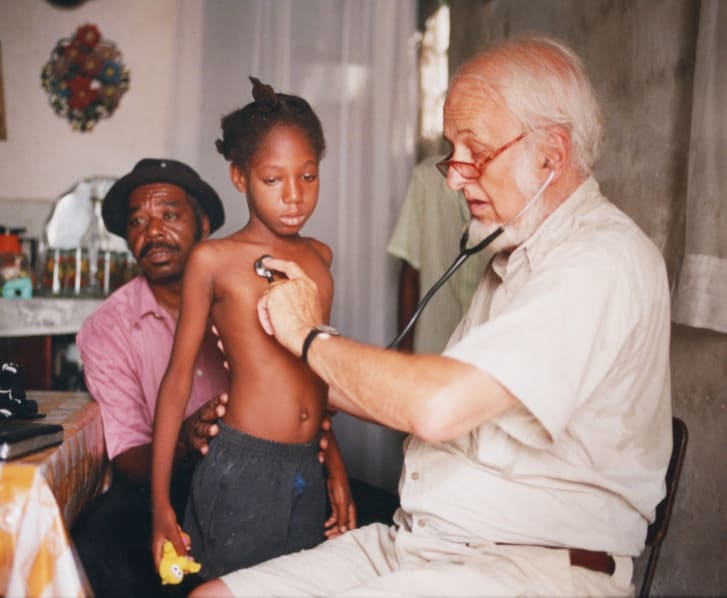

In 2001, MFP expanded its mission to provide medical care to Haitian women and children in rural areas. In March 2010, MFP initiated a women’s health initiative for the upper Artibonite region supported by a coalition of local women’s organizations. The program is based at the Alma Mater Hospital in Gros Morne, with mobile units that travel to remote dispensaries. As of August 2023, we have screened and treated more than 10,000 women in the upper Artibinite region. The MFP Women’s Health Initiative is one of the largest and most comprehensive in Haiti and is a model for cost-effective delivery of women’s health care in an underdeveloped area.

Broadening our care for victims of war trauma and torture we opened the MFP Health Center for Torture Victims in 2009, now located at the Grace Medical Center Hospital in West Baltimore. With our service partners, we provide medical, psychological, and social services to patients who have been tortured in other countries and are seeking asylum in the United States.

MFP is an advocacy organization as well, and has released a number of landmark reports on the health crisis in the Iraq and on state-sponsored torture. Two award-winning film documentaries, William LiPera’s “Children of the Cradle”, and Susan Meiselis’ “Opening Hearts”, described MFP’s work with Iraqi Children. MFP physicians have appeared on television and radio news, and have testified before U.S. Congressional and U.N. Committees concerning our work in war zones, Haiti, and in the United States.

MFP is supported by donations from individuals, by foundation grants, and bequests. We do not accept financial support from parties to armed conflicts.

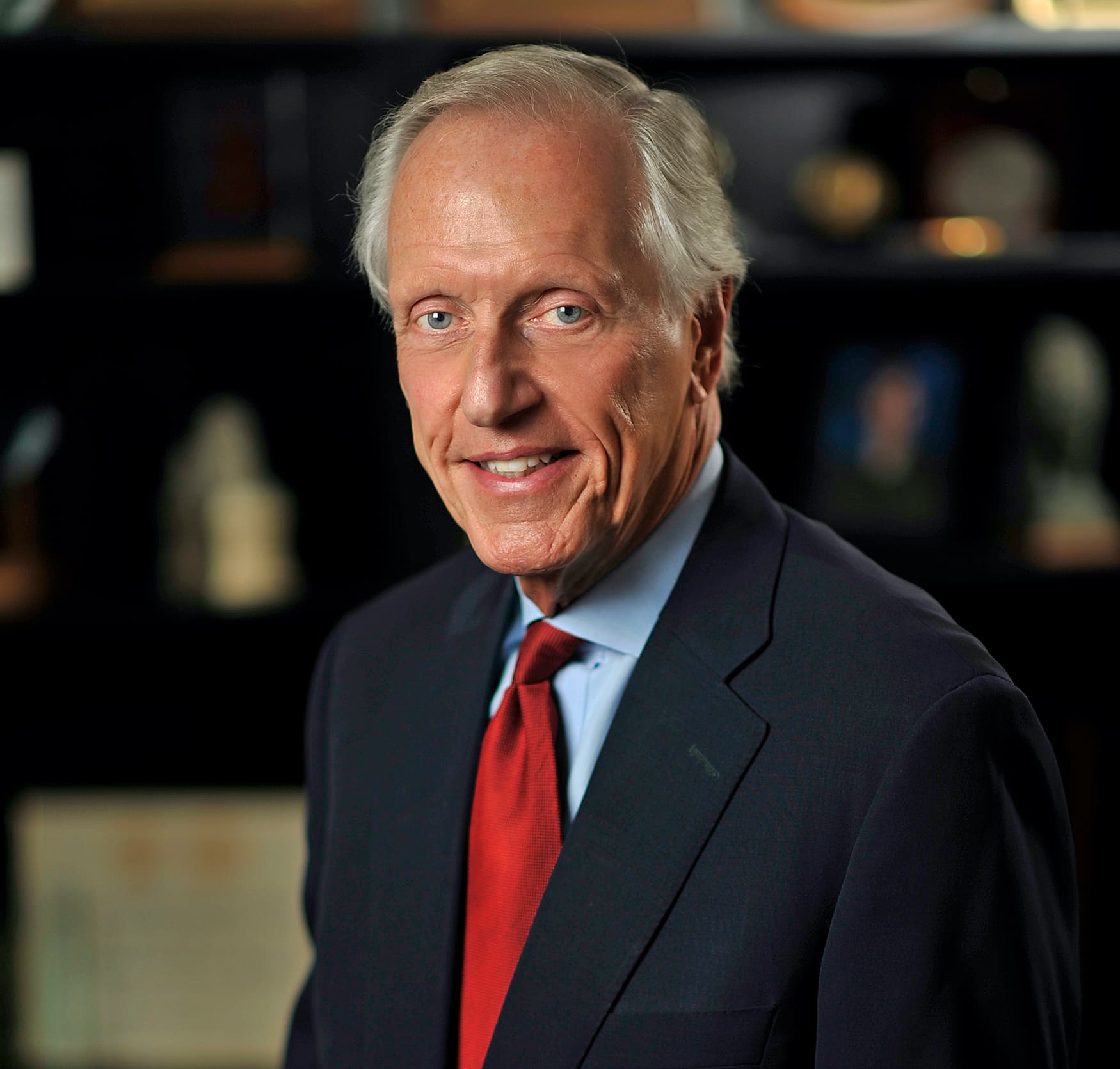

Founder and Director- Michael Viola, M.D.

McGill Medicine Focus Spring 2019

By Philip Fine

Michael Viola, MD CM’64, is both healer and activist.

The recipient of the 2018 Medicine Alumni Global Award for Community Service has treated patients in war-torn Iraq and Bosnia, set up cancer detection clinics in Haiti, and corroborated the stories of torture victims.

The founder of the medical relief agency Medicine for Peace (MFP) now divides his time between the MFP office in DC and his clinic in Baltimore, but grew up in Revere, a Boston suburb that knew some rough characters. He remembers a “near-idyllic childhood,” due in large part to a nurturing extended Italian-American family. His local doctor encouraged his interest in medicine, but young Michael, who had read at the library about the international development work of Albert Schweitzer and the war exploits of Norman Bethune, wanted to go beyond the neighborhood family practice.

He studied medicine in Montreal, a city where Bethune had once worked. McGill, he says, gave him his clinical skills and taught him to treat the practice of medicine with reverence. “They instilled the idea that you were privileged to take care of another human being.”

Returning to Boston each summer, he worked in the lab of Bernard Lown, a Harvard researcher who developed the direct-current defibrillator but was also the dean of the anti-nuclear movement. “He was a very controversial guy. The thought then was that physicians should not be active in politics.”

Lown’s credo, “Never be silent in the presence of wrong,” has framed Viola’s activist work.

In 1991, when the first Gulf War began, Viola was Director of the Cancer Center at the State University of New York. As he and his wife Kathleen Crane watched aerial footage of bombings on TV, they knew that Baghdad, with five million inhabitants at the time, was experiencing tragedy on the ground. He called a physician friend in Jordan who had come back from Iraq. He talked of there being no electricity, no water, and children wading through knee-deep sewage. It was a public-health crisis waiting to happen.

“Sometimes it is a little moment in your life when you do something. And I did a crazy thing. I wrote to the Iraqi ambassador in the US.” Viola wanted to bring an American team to Iraq to help treat civilians and document their illnesses. “And that’s how it all started.”

In Iraq, he would run into a New York Times reporter. The story of doctors witnessing severe malnutrition and widespread disease would land on page one. MFP would go on to publish a number of in-depth reports on the health crisis in Iraq.

In 1995, MFP focused on Bosnia. In the wake of the Srebrenica massacre, where more than 8,000 Muslim men and boys were killed, they launched a school-based mental health project and remained in Bosnia for more than five years. “That presence gave people comfort.”

MFP’s more recent humanitarian work operates outside the theatre of war. In Haiti, they established a cervical cancer detection program in mobile clinics, and helped improve treatment infrastructure. And stateside, they’ve been meeting with victims of torture. The detailed examinations have secured asylum for every patient they’ve seen.

While most would think documenting the effects of torture would be trying for examining physicians, Viola projects admiration for the people he meets and their ability to call out a wrong. “They inhabit a different moral universe. I’ve never met a torture victim who regretted what they did. They’re an extraordinarily courageous group of people.”

Michael Viola, through his community service, has shown that a physician not only diagnoses ailments but can identify human rights abuses, and treats more than just individuals but can rally other doctors to help heal entire populations.

Claude Allen

James Chen, MD, PhD

Kathleen Crane

Brittany Galvin, RN, NP

William Schaffner, M.D.

Michael V. Viola, M.D.

Monika Viola

Advisory Board

Auxiliary Bishop

Detroit, MI

Intercultural Counselling Connection

Baltimore, MD

President

Jordanian Red Cross and

Red Crescent Society

Amman, Jordan

Belfast, Northern Ireland

Nobel Peace Prize, 1977

Portland, ME

Gros Morne, Haiti

Stanley Medical Research Institute

Rockville, MD